Member State of the European Union

| EU Member State | |

|---|---|

_EN.svg.png)

|

|

| Category | Sovereign states[1] |

| Location | European Union |

| Created | 1952/1958 |

| Number | 27 (as at 1 January 2007) |

| Possible types | Republics (20) |

| Monarchies (7) | |

| Populations | 416,333–81,757,595 |

| Areas | 316–674,843 km² |

| Government | Parliamentary representative democracy (23) |

| Presidential representative democracy (1) | |

| Semi-presidential representative democracy (3) | |

A Member State of the European Union is a state that has signed and ratified the treaties of the European Union (EU) and has thus taken on the privileges and obligations of EU membership. Unlike membership of an international organisation, being an EU member state places a country under binding laws in exchange for representation in the EU's legislative and judicial institutions. On the other hand, unlike being a member of a federation (such as a U.S. state) EU states maintain a great deal of autonomy, including maintaining their national militaries and foreign policy (where they have not agreed to European action in that area[2]).

Since 2007 there have been twenty-seven EU member states. Six core states founded the EU's predecessor, the European Economic Community, in 1957 and the remaining states joined in subsequent enlargements. Before being allowed to join the EU, a state must fulfil the economic and political conditions generally known as the Copenhagen criteria. These basically require that a candidate to have a democratic, free market government together with the corresponding freedoms and institutions, and respect the rule of law. Enlargement of the Union is conditional upon the agreement of each existing member and the candidate's adoption of all pre-existing EU law.

There is a wide disparity in the size, wealth and political system of member states, but all have equal rights. While in some areas majority voting takes place where larger states have more votes than smaller ones, smaller states have disproportional representation compared to their population. As of 2010 no member state has withdrawn or been suspended from the EU.

Contents |

List

| Flag | State | Constitutional name(s) | Joined | Population | km² | GDP[3] | Gini | HDI | Capital | Languages | Territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Republik Österreich | 1995 | 8,372,930[4] | 83,871 | 38,838[5] | 29.1[6] | 0,955[7] | Vienna | German | – | |

| Belgium | Koninkrijk België Royaume de Belgique Königreich Belgien |

Founder | 10,827,519[4] | 30,528 | 35,421[5] | 33.0[6] | 0,953[7] | Brussels | Dutch French German |

– | |

| Bulgaria | Република България | 2007 | 7,576,751[4] | 110,910 | 11,900[5] | 29.2[6] | 0,840[7] | Sofia | Bulgarian | – | |

| Cyprus | Κυπριακή Δημοκρατία Kıbrıs Cumhuriyeti |

2004 | 801,851[4] | 9,251 | 28,544[5] | 31.2[6] | 0,914[7] | Nicosia | Greek Turkish |

3 excluded

|

|

| Czech Republic | Česká republika | 2004 | 10,512,397[4] | 78,866 | 24,093[5] | 25.8[6] | 0,903[7] | Prague | Czech | – | |

| Denmark | Kongeriget Danmark | 1973 | 5,547,088[4] | 43,094 | 35,757[5] | 24.7[6] | 0,955[7] | Copenhagen | Danish |

2 excluded

|

|

| Estonia | Eesti Vabariik | 2004 | 1,340,274[4] | 45,226 | 17,908[5] | 36.0[6] | 0,883[7] | Tallinn | Estonian | – | |

| Finland | Suomen tasavalta Republiken Finland |

1995 | 5,350,475[4] | 338,145 | 33,555.[5] | 26.9[6] | 0,959[7] | Helsinki | Finnish Swedish |

1

|

|

| France | République française | Founder | 64,709,480[4] | 674,843 | 33,678[5] | 32.7[6] | 0,961[7] | Paris | French |

6 + 6 excluded

|

|

| Germany | Bundesrepublik Deutschland | Founder[t 5] | 81,757,595[4] | 357,050 | 34,212[5] | 28.3[6] | 0,947[7] | Berlin | German | – | |

| Greece | Ελληνική Δημοκρατία | 1981 | 11,125,179[4] | 131,990 | 29,881[5] | 34.3[6] | 0,942[7] | Athens | Greek | – | |

| Hungary | Magyar Köztársaság | 2004 | 10,013,628[4] | 93,030 | 18,566[5] | 30.0[6] | 0,879[7] | Budapest | Hungarian | – | |

| Ireland | Éire Ireland[t 6] |

1973 | 4,450,878[4] | 70,273 | 39,468[5] | 34.3[6] | 0,965[7] | Dublin | Irish English |

– | |

| Italy | Repubblica italiana | Founder | 60,397,353[4] | 301,318 | 29,109[5] | 36.0[6] | 0,951[7] | Rome | Italian | – | |

| Latvia | Latvijas Republika | 2004 | 2,248,961[4] | 64,589 | 14,254[5] | 35.7[6] | 0,866[7] | Riga | Latvian | – | |

| Lithuania | Lietuvos Respublika | 2004 | 3,329,227[4] | 65,303 | 16,542[5] | 35.8[6] | 0,870[7] | Vilnius | Lithuanian | – | |

| Luxembourg | Grand-Duché de Luxembourg Großherzogtum Luxemburg Groussherzogtum Lëtzebuerg |

Founder | 502,207[4] | 2,586 | 78,395[5] | 30.8[6] | 0,960[7] | Luxembourg | French German Luxembourgish |

– | |

| Malta | Repubblika ta' Malta Republic of Malta |

2004 | 416,333[4] | 316 | 23,583[5] | 25.8[6] | 0,902[7] | Valletta | Maltese English |

– | |

| Netherlands | Koninkrijk der Nederlanden[t 7] | Founder | 16,576,800[4] | 41,526 | 39,937[5] | 30.9[6] | 0,964[7] | Amsterdam[t 8] | Dutch |

2 excluded

|

|

| Poland | Rzeczpospolita Polska | 2004 | 38,163,895[4] | 312,683 | 18,072[5] | 34.9[6] | 0,880[7] | Warsaw | Polish | – | |

| Portugal | República Portuguesa | 1986 | 10,636,888[4] | 92,391 | 21,858[5] | 38.5[6] | 0,909[7] | Lisbon | Portuguese |

2

|

|

| Romania | România[t 9] | 2007 | 21,466,174[4] | 238,391 | 11,917[5] | 31.5[6] | 0,837[7] | Bucharest | Romanian | – | |

| Slovakia | Slovenská republika | 2004 | 5,424,057[4] | 49,037 | 21,244[5] | 25.8[6] | 0,880[7] | Bratislava | Slovak | – | |

| Slovenia | Republika Slovenija | 2004 | 2,054,119[4] | 20,273 | 27,654[5] | 31.2[6] | 0,929[7] | Ljubljana | Slovenian | – | |

| Spain | Reino de España | 1986 | 46,087,170[4] | 506,030 | 29,689[5] | 34.7[6] | 0,955[7] | Madrid | Spanish |

1

|

|

| Sweden | Konungariket Sverige | 1995 | 9,347,899[4] | 449,964 | 35,964[5] | 25.0[6] | 0,963[7] | Stockholm | Swedish | – | |

| United Kingdom | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland |

1973 | 62,041,708[4] | 244,820 | 34,618[5] | 36.0[6] | 0,947[7] | London | English[t 10] |

1 + 16 excluded

|

- Notes

- ↑ Northern Cyprus is not recognised by the EU, so it is de jure part of the Republic of Cyprus and the EU, but de facto is outside the control of both entities and operates as an independent state recognised only by Turkey. See Cyprus dispute.

- ↑ De jure part of the Republic of Cyprus and the EU, but de facto is outside of the control of both due to the ongoing Cyprus dispute. It is administered by the United Nations.

- ↑ Greenland left the then-EEC in 1985.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 See Article 355(1) of the Treay on the Functioning of the European Union. [1]

- ↑ On 3 October 1990, the constituent states of the former German Democratic Republic acceded to the Federal Republic of Germany, automatically becoming part of the EU.

- ↑ Constitutional name of Ireland is Ireland, "Republic of" is only used to distinguish it from the north.

- ↑ "Kingdom of the Netherlands" is correct. See this article. However, only Netherlands (i.e. the European part) is fully subject to EU law.

- ↑ Amsterdam is the constitutional capital, however The Hague is the seat of government.

- ↑ Official name is just Romania

- ↑ English is the de facto national language of the UK. Recognized regional languages are Irish, Ulster Scots, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Welsh and Cornish.

Enlargement

Enlargement has been a principal feature of the Union's political landscape. The EU's predecessors were founded by the "Inner Six", those countries willing to forge ahead with the Community while others remained sceptical. It was but a decade before the first countries changed their policy and attempted to join the Union, which led to the first scepticism of enlargement. French President Charles de Gaulle feared British membership would be an American Trojan horse and vetoed its application. It was only after de Gaulle left office and a 12-hour talk by British Prime Minister Edward Heath and French President George Pompidou took place did Britain's third application succeed (in 1970).[8][9][10]

Applying in 1969 were Britain, Ireland, Denmark and Norway. Norway however declined to accept the invitation to become a member,[11] with the electorate voting against it[12] leaving just the UK, Ireland and Denmark to join.[8] But despite the setbacks, and the withdrawal of Greenland from Denmark's membership in 1985,[13] three more countries would join the Communities before the end of the Cold War.[8] In 1987, the geographical extent of the project was tested when Morocco applied, and was rejected as it was not considered a European country.[14]

1990 saw the Cold War drawing to a close, and East Germany was welcomed into the Community as part of a reunited Germany. Shortly after, the previously neutral countries of Austria, Finland and Sweden acceded to the new European Union,[8] though Switzerland, which applied in 2002, froze its application due to opposition from voters[15] while Norway, which had applied once more, had its voters reject membership again.[16] Meanwhile, the members of the former Eastern bloc and Yugoslavia were all starting to move towards EU membership. 10 of these joined in a "big bang" enlargement on 1 May 2004 symbolising the unification of East and Western Europe in the EU.[17]

| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

Policies and issues

|

|

Foreign relations

|

2007 saw the latest members, Bulgaria and Romania, accede to the Union and the EU has prioritised membership for the Western Balkans. Croatia, Macedonia and Turkey are all formal, acknowledged candidates. Iceland has also applied for membership.[18] Turkish membership, pending since the 1980s, is a more contentious issue but it entered negotiations in 2004.[19] There are at present no plans to cease enlargement; according to the Copenhagen criteria, membership of the European Union is open to any European country that is a stable, free market liberal democracy that respects the rule of law and human rights. Furthermore, it has to be willing to accept all the obligations of membership such as adopting all previously agreed law (the 170,000 pages of acquis communautaire) and joining the euro.[20] As well as enlargement to new countries, the EU can expand by having territories of member states which are outside the EU integrate more closely (for example in respect to the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles) or a territory of a member state seceded then rejoined (see withdrawal below).

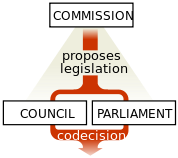

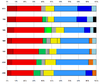

Representation

Each state has representation in the institutions of the European Union. Full membership gives the government of a Member State a seat in the Council of the European Union and European Council. When decisions are not being taken by consensus, votes are weighted so that a country with a greater population has more votes within the Council than a smaller country (although not exact, smaller countries have more votes than their population would allow relative to the largest countries). The Presidency of the Council of the European Union rotates between each of the member states, allowing each state six months to help direct the agenda of the EU.

Similarly, each state is assigned seats in Parliament according to their population (again, with the smaller countries receiving more seats per inhabitant than the larger ones). The members of the European Parliament have been elected by universal suffrage since 1979 (before which they were seconded from national parliaments).

The national governments appoint one member each to the European Commission (in accord with its president), the European Court of Justice (in accord with other members) and the Court of Auditors. Historically, larger Member States were granted an extra Commissioner. However, as the body grew, this right has been removed and each state is represented equally. The six largest states are also granted an Advocates General in the Court of Justice. Finally, the governing of the European Central Bank is made up of the governors of each national central bank (who may or may not be government appointed).

The larger states traditionally carry more weight in negotiations, however smaller states can be effective impartial mediators and citizens of smaller states are often appointed to sensitive top posts to avoid competition between the larger states. This, together with the disproportionate representation of the smaller states in terms of votes and seats in parliament, gives the smaller EU states a greater clout than normally attributed to a state of their size. However most negotiations are still dominated by the larger states. This has traditionally been largely through the "Franco-German motor" but the Franco-German role influence has diminished slightly following the influx of new members in 2004 (see G6).[21]

Sovereignty

- 1. In accordance with Article 5, competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States.

- 2. The Union shall respect the equality of Member States before the Treaties as well as their national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional, inclusive of regional and local self-government. It shall respect their essential State functions, including ensuring the territorial integrity of the State, maintaining law and order and safeguarding national security. In particular, national security remains the sole responsibility of each Member State.

- 3. Pursuant to the principle of sincere cooperation, the Union and the Member States shall, in full mutual respect, assist each other in carrying out tasks which flow from the Treaties. The Member States shall take any appropriate measure, general or particular, to ensure fulfilment of the obligations arising out of the Treaties or resulting from the acts of the institutions of the Union. The Member States shall facilitate the achievement of the Union's tasks and refrain from any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the Union's objectives.

The founding treaties state that all Member States are indivisibly sovereign and of equal value. However, the EU does follow a supranational system (similar to federalism) in nearly all areas (previously limited to European Community matters). Combined sovereignty is delegated by each member to the institutions in return for representation within those institutions. This practice is often referred to as "pooling of sovereignty".[22] Those institutions are then empowered to make laws and execute them at a European level. If a state fails to comply with the law of the European Union, it may be fined or have funds withdrawn. In extreme cases, there are provisions for the voting rights or membership of a state to be suspended (see Suspension above).

In contrast to other organisations, the EU's style of integration has "become a highly developed system for mutual interference in each other's domestic affairs"[23] However on defence and foreign policy issues (and, pre Lisbon Treaty, police and judicial matters) less sovereignty is transferred, with issues being dealt with by unanimity and cooperation.

Yet, as sovereignty still originates from the national level, it may be withdrawn by a Member State who wishes to leave. Hence, if a law is agreed that is not to the liking of a state, it may withdraw from the EU to avoid it. This however has not happened as the benefits of membership are often seen to outweigh any negative impact of certain laws. Furthermore, in realpolitik, concessions and political pressure may lead to a state accepting something not in their interests in order to improve relations and hence strengthen their position on other issues.

The question of whether EU law is superior to national law is subject to some debate. The treaties do not give a judgement on the matter but court judgements have established EU's law superiority over national law and it is affirmed in a declaration attached to the Treaty of Lisbon (the European Constitution would have fully enshrined this). Some national legal systems also explicitly accept the Court of Justice's interpretation, such as France and Italy, however in Poland it does not override the national constitution, which it does in Germany. The exact areas where the member states have given legislative competence to the EU are as followed. Every area not mentioned remains with member states;

| As outlined in Part I, Title I of the consolidated Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union: | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

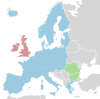

Opt-outs

A number of states are less integrated into the EU than others. In most cases this is because those states have gained an opt-out from a certain policy area. The most notable is the opt-out from the Economic and Monetary Union, the adoption of the euro as sole legal currency. Most states outside the Eurozone are obliged to adopt the euro when they are ready, but Denmark and the United Kingdom (and Sweden in an informal manner) have obtained the right to retain their own independent currencies.

Ireland and the United Kingdom also do not participate in the Schengen Agreement, which eliminates internal EU border checks. Denmark has an opt out from the Common Security and Defence Policy; Denmark, Ireland and the UK have an opt-out on police and justice matters and Poland and the UK have an opt out from the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Political systems

The entry criteria for the EU is limited to liberal democracies; however, the exact political system of a state is not limited. Thus, each state has its own system based upon its historical evolution. Seven states are constitutional monarchies, meaning they have a monarchy although political powers are practiced by elected politicians. Of the republics, Cyprus operates a presidential system (the president is head of state and government) and three others operate a semi-presidential system (competencies shared between the president and prime minister). All remaining republics and all the monarchies operate a parliamentary system whereby the head of state (president or monarchy) plays only a ceremonial role.

There are also differences in regional and local government with some states such as Germany and Belgium being formed as a federation, others such as Poland and Malta being a unitary state and countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom devolving powers to regions. States such as France have a number of overseas territories, retained from their former empires. Some of these territories such as French Guiana are part of the EU while others are related to the EU or outside it; such as the Falkland Islands.

Withdrawal and suspension

As of 2010 no state has withdrawn from the EU. However Greenland, as a territory, did so. The Lisbon Treaty made the first provision of a member state to leave, through procedure of negotiated withdrawal. The procedure for a state to leave is outlined in TEU Article 50 which also makes clear that "Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements."

There are a number of independence movements within member states (such as Catalonia, Flanders and Scotland). Were a province of a member state to secede but wish to remain in the EU, it would have to reapply to join as if it were a new country applying from scratch.[24]

TEU Article 7 provides for the suspension of certain rights of a member state. Introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam, Article 7 outlines that if a member persistently breaches the EU's founding principles (liberty, democracy, human rights and so fourth, outlined in TEU Article 2) then the European Council can vote to suspend any rights of membership, such as voting and representation as outlined above. Identifying the breach requires unanimity (excluding the state concerned), but sanctions require only a qualified majority.[25]

The state in question would still be bound by the obligations treaties and the Council acting by majority may alter or lift such sanctions. The Treaty of Nice included a preventative mechanism whereby the Council, acting by majority, may identify a potential breach and make recommendations to the state to rectify it before action is taken against it as outlined above.[25]

Related states

There are a number of countries with strong links with the EU, similar to elements of membership. Following Norway's failure to join the EU, it became one of the members of the European Economic Area which also includes Iceland and Liechtenstein (all former members have joined the EU and Switzerland rejected membership). The EEA links these countries into the EU's market, extending the four freedoms to these states. In return, they pay a membership fee and have to adopt most areas of EU law (which they do not have direct impact in shaping). The democratic repercussions of this have been described as "fax democracy" (waiting for new laws to be faxed in from Brussels rather than being involved).[26]

A different example is Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has been under international supervision. The High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina is an international administrator who has wide ranging powers over Bosnia and Herzegovina to ensure the peace agreement is respected. The High Representative is also the EU's representative, and is in practice appointed by the EU. In this role, and since a major ambition of Bosnia and Herzegovina is to join the EU, the country has become a de facto protectorate of the EU. The EU appointed representative has the power to impose legislation and dismiss elected officials and civil servants, meaning the EU has greater direct control over Bosnia and Herzegovina than its own citizens. Indeed the state's flag was inspired by the EU's flag.[27] In the same manner as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo is under heavy EU influence, particularly after the de facto transfer from UN to EU authority. In theory Kosovo is supervised by EU missions, with justice and policing personal training and helping to build up the state institutions. However the EU mission does enjoy certain executive powers over the state and has a responsibility to maintain stability and order.[28]

However there is also the largely defunct term of associate member. It has occasionally been applied to states which have signed an association agreement with the EU. Associate membership is not a formal classification and does not entitle the state to any of the representation of free movement rights that full membership allows. The term is almost unheard of in the modern context and was primarily used in the earlier days of the EU with countries such as Greece and Turkey. Turkey's association agreement was the 1963 Ankara Agreement, from this it is drawn that Turkey became an associate member on that day.[29][30] Present association agreements include the Stabilisation and Association Agreements with the western Balkans; these states are no longer termed "associate members".

See also

- Countries bordering the European Union

- European Commission Representation in Ireland

- Special Member State territories

- Currencies of the European Union

|

||||||||

References

- ↑ See section on sovereignty for details on the extent to which sovereignty is shared.

- ↑ EU foreign policy is agreed case by case where every member state agrees to a common position. Thus a member state can veto a foreign policy it does not agree with and agreed policy tends to be lose and infrequent.

- ↑ at purchasing power parity, per capita, in international dollars (rounded)

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 "Eurostat Population Estimate" (in English). Eurostat. 2010-01-01. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&language=en&pcode=tps00001&tableSelection=1&footnotes=yes&labeling=labels&plugin=1. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 Report for Selected Countries and Subjects IMF

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/indicators/161.html

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 Human Development Report 2009 - HDI rankings, UNDP, accessed 1 June 2010

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Britain shut out". BBC News. 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/uk/2001/uk_and_europe/1958_1969.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "1971 Year in Review, UPI.com"

- ↑ Ever closer union: joining the Community - BBC

- ↑ Telegraph.co.uk

- ↑ European Commission (10 November 2005). "The History of the European Union: 1972". http://europa.eu/abc/history/1972/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ European Commission (10 November 2005). "1985". The History of the European Union. http://europa.eu/abc/history/1985/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ "W. Europe Bloc Bars Morocco as a Member". Los Angeles Times. 21 July 1987. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/58410310.html?dids=58410310:58410310&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=Jul+21%2C+1987&author=&pub=Los+Angeles+Times+(pre-1997+Fulltext)&desc=W.+Europe+Bloc+Bars+Morocco+as+a+Member&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ British Embassy, Berne (4 July 2006). "EU and Switzerland". The UK & Switzerland. http://www.britishembassy.gov.uk/servlet/Front?pagename=OpenMarket/Xcelerate/ShowPage&c=Page&cid=1085326325096. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ↑ European Commission (10 November 2005). "The History of the European Union: 1994". http://europa.eu/abc/history/1994/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ "History of the European Union". Europa (web portal). http://europa.eu/abc/history/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "Enlargement- Countries". Europa (web portal). http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/countries/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "Q&A: Turkey's EU entry talks". BBC News. 11 December 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4107919.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "Accession criteria". Europa (web portal). http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/enlargement_process/accession_process/criteria/index_en.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ Peel, Q et al (26 March 2010) Deal shows Merkel has staked out strong role, Financial Times

- ↑ http://www.answers.com/topic/pooled-sovereignty

- ↑ Cooper, Robert (7 April 2002) Why we still need empires, The Guardian

- ↑ Happold, Matthew (1999) Scotland Europa: independence in Europe?, Centre for European Reform, Accessed 14 June 2010 (PDF)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Suspension clause, Europa glossary, accessed 1 June 2010

- ↑ Ekman, Ivar (27 October 2007). "In Norway, EU pros and cons (the cons still win)". International Herald Tribune. http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/10/26/news/norway.php. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ Chandler, David (20 April 2006). "Bosnia: whose state is it anyway?". Spiked Politics. http://www.spiked-online.com/Articles/0000000CB02A.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ↑ Kurti, Albin (2 September 2009). "Comment: Causing damage in Kosovo". EUobserver. http://euobserver.com/9/28602. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ "EU-Turkey relations". EurActiv. 14 November 2005. http://www.euractiv.com/en/enlargement/eu-turkey-relations/article-129678. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ "Turkey's Tigers, Report Card: Turkey and EU Membership?: Introduction". Public Broadcasting Service. 10 June 2008. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wideangle/episodes/turkeys-tigers/report-card-turkey-and-eu-membership/introduction/583/. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

External links

- Member States – Europa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||